Sign the petition and join us in calling on Australian and International clothing brands to:

- Rapidly accelerate actions to start paying a living wage to the women who make our clothes.

- Honour your living wage commitment, and take the steps so workers are actually paid a living wage.

- Urgently implement better purchasing practices and separate labour costs from price negotiations to protect workers wages.

- Prioritise undertaking a wage gap analysis to find out the gap between the current wage and the living wage, then bridge the gap.

Brands are paying poverty wages

Kmart in particular is swimming in cash, making a whopping $10.6 billion last year. Yet, the women working in Bangladeshi factories making Kmart’s clothes are paid as little as $6 per day – nowhere near enough to stay afloat.

For garment workers, real wages haven’t risen for years… but brands’ revenue reaches ‘sun-believable’ heights.

Many of us are treading water, noticing our income doesn’t stretch as far as it used to, from paying more at the supermarket to energy bills.

At the same time, the women who make our clothes in countries like Bangladesh and Cambodia are also facing a cost-of-living crisis, barely staying afloat. It’s a world-wide problem – the prices for everyday items keeps rising but wages do not.

Women like Kakoli struggle to afford everyday necessities, unable to make ends meet without overtime. Even though she works many hours in a factory in Dhaka, she still relies on her family back home to send her money.

Join us to turn up the heat on wages, insist brands start paying a living wage now.

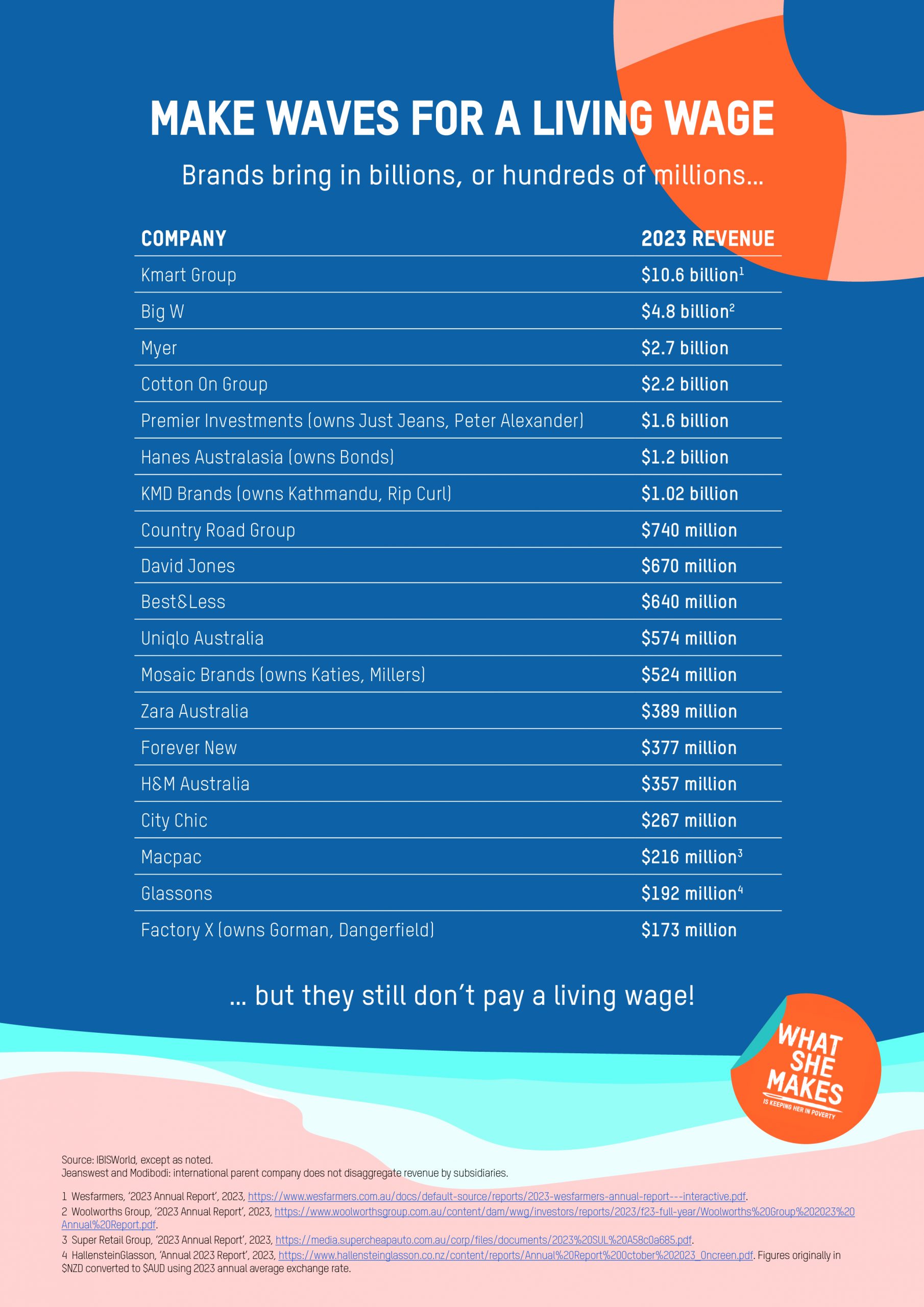

Fashion brands reeled in $25.7 billion in 2023

Kakoli’s story

When brands fail to act on living wages, there’s nothing to celebrate for women like Kakoli. Corporate greed and a system built on entrenched exploitation leaves the women who make our clothes struggling to survive.

Kakoli is 23 years old and works in factory as a garment worker tasked with cutting yarn.

She lives alone in Dhaka, after leaving her family behind in her home village. At 19, she was the first in her family to move to the capital in pursuit of better opportunities.

“I work all day standing. I feel pain in my legs, as I always stand while working. I go to the doctor, my leg used to swell up, and now they hurt.”

When there is no overtime available, Kakoli struggles to afford basic necessities.

If Kakoli was paid a living wage, she wouldn’t need to rely on overtime.

“We cannot live with an 8000 taka [$110 AUD] salary as everything is expensive, like room rent and food. If our salary increases, it would be better as everything is expensive.”

As the cost-of-living impacts people worldwide, Kakoli struggles to be able to send money back to her parents and siblings in the village. Her family now needs to sometimes send her money.

“With the clothes I make and the salary I get from this, it’s hard to live and eat properly.”

Time is up for brands to pay Kakoli, and millions of women like her, a living wage.

Poverty Pay v Waves of Wealth

With revenue like this, there’s no excuse for not prioritising a living wage.

Tell brands it’s time for a fresh look

We’ve been running a living wage campaign for seven years, building on decades of activism alongside garment workers to demand wages and workers’ rights are part of the conversation for companies and consumers alike – and we’ve been making waves.

Together we’ve pushed brands to make a commitment to a living wage, yet they are all at sea when it comes to taking the actions required to actually pay a living wage. We’re now drawing a line in the sand. It’s high (tide) time for brands to start paying a living wage to the women who make our clothes.

Join us to demand brands prioritise garment workers and start paying a living wage now!

How can brands start paying a living wage?

We’ve chartered this course for a long time, and now it’s crucial brands navigate these waters to bring plans for a living wage to fruition. Here’s what they must do:

Wage Gap Analysis

In 2022, brands were asked to take a close look at workers’ wages by conducting a ‘wage gap analysis,’ which involves calculating the difference between current worker wages and the living wage, then making a plan to bridge that gap.

We’re still waiting for Big W, H&M, Jeanswest, Kmart and Target, Modibodi, Uniqlo and Zara to agree to undertake a wage gap analysis.

Separate Labour Costs

Four years ago, we urged brands to improve their ruthless purchasing practices – the way they place orders and the prices they pay to factories to make clothes. To improve wages, brands can ‘ring fence’ wages from price negotiations, protecting the wage component so workers’ wages don’t sink any lower.

Jeanswest and Uniqlo still haven’t even agreed to separate labour costs. And although these brands have promised to ring fence wages – Big W, Bonds, City Chic, Country Road, David Jones, Forever New, Just Group, Myer, Modibodi, Zara – they are yet to demonstrate it’s been implemented.

We’d love to see newly added brands Kathmandu and Rip Curl (owned by KMD Brands) commit to ring fence wages soon too.

Publish Factory List

And while we’re at it, Just Group, Modibodi and Zara still bury their factory lists deep in the sand, never bringing them up to sunlight. We are way past the time when transparency became the industry norm.

Newly added brand Glassons also needs to publish the names and locations of their suppliers. We are way past the time when supply chain transparency became the industry norm.

Christmas at a glance

We’ve been calling out brands at Christmas since 2013. The first Naughty or Nice List was in the year the Rana Plaza factory collapsed and we called on brands to join the Bangladesh Accord. Since then, the List has looked at transparency, living wage and wage gap analysis. Thanks to tireless campaigning from workers, Oxfam and supporters like you, brand have come a long way. You can look back on previous lists here:

2023 Christmas WishlistFAQ

Where is your revenue data from?

Statements are based on company data available from IBISWorld, an industry research provider. IBISWorld collects their Australian data from publicly available sources, such as company Annual Reports, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, sector-level data from industry federations and regulators, as well as real-world advice, feedback and updates on operating conditions from contacts in relevant industries.

When using ‘revenue’ Oxfam refers to the total income a business generates through sales and other activities such as investment dividends. ‘Profit/s’ refers to revenues minus expenses and tax.