People often tell us that the bank response to their email about land grabs is confusing and full of jargon. Lately we’ve had a lot of questions about ANZ. Below is a recap of what ANZ has done, and not done, since Oxfam launched its Banking on Shaky Ground report in April.

Background: The ANZ and Phnom Penh Sugar Case

In January 2014 Fairfax newspapers revealed that ANZ had loaned millions of dollars to Phnom Penh Sugar (PPS) for its sugarcane plantation in Kampong Speu, Cambodia. PPS has been linked to food shortages, widespread use of child labour, arbitrary arrests and intimidation, and dangerous working practices.

The loan came from ANZ Royal – ANZ’s Cambodian arm. ANZ Royal is majority (55%) owned by ANZ. Two Cambodia-based NGOs report that ANZ’s Australian headquarters directly approved the loan.

In 2010 and 2011 PPS officials accompanied by military and police seized hundreds of families’ lands and crops. PPS, and its subsidiary, now control almost 23,000 hectares through three land concessions. PPS is owned by an influential senator and the Cambodian government granted PPS access to the land without acknowledging the existing rights of local people. There are various allegations of corruption around the deal.

ANZ links to land grabs

ANZ has stated that it loaned money for the PPS sugar mill. PPS describes the mill as part of ‘a single operation’, so it is an intrinsic part of its Kampong Speu sugar plantation. The PPS mill stands side-by-side hectares of sugarcane, on the same land concession. It is owned and managed by members of the same powerful family. The mill exists to process sugar that is now where locals once grew food.

ANZ did not uphold its human rights commitments before investing, and then cut and ran. The Cambodian media and a report by consultants for ANZ both raised concerns about PPS and land rights violations before ANZ financed the loan. Yet ANZ headquarters still approved a loan to PPS (estimated at $40 million). In 2014 July PPS suddenly repaid the loan and ANZ cut and ran.

Affected community members have not received adequate compensation. Fair compensation involves a whole-of-community approach based on the systematic valuation of property, livelihoods or other land uses. However, in the PPS case some farmers received just $50 – despite losing their livelihoods, their family’s key food source and their social safety net for current and future years. People were threatened into taking payments, others were offered nothing. Many families lost their farming land and were forced onto small 40x50m residential plots with poor soils and water access.

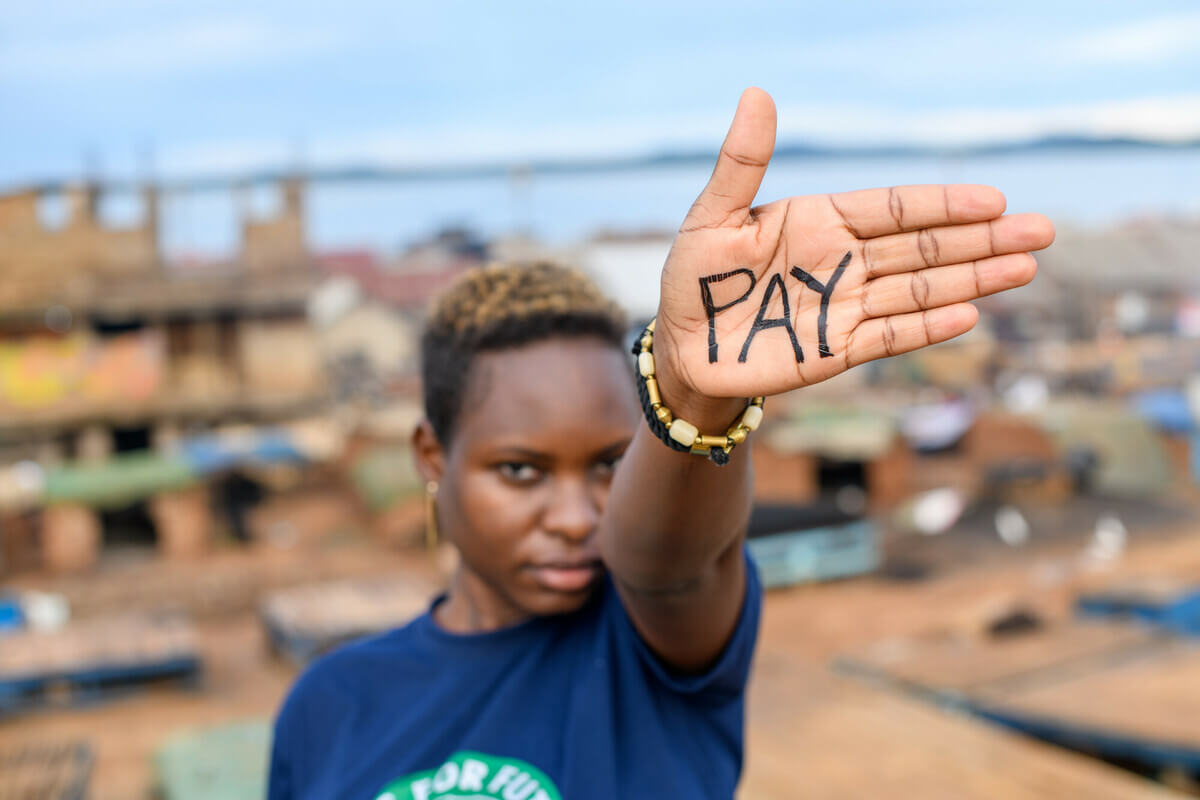

Cambodian NGO, Equitable Cambodia, conservatively estimates the cost of loss of private land and income alone at around 11 million US dollars. They’ve called on ANZ to return its profit on the loan to the community – estimated at $5 million. Something up to now that ANZ has refused to do.

Life for affected communities has not improved.

ANZ is well-informed about PPS links to human rights violations. It has met community members and at least three different NGOs about the case. ANZ recently said that it will respond to NGO concerns primarily through its existing sensitive sector policies. Yet ANZ doesn’t have a sensitive sector policy for agriculture, and hasn’t committed to creating one.

Five months after its relationship with PPS ended, ANZ has started sending emails to Oxfam supporters marked ‘private and confidential’ making new claims about its earlier efforts to engage the company. The reality however for affected communities has not changed, nor has the responsibility that ANZ has to rectify its role in the injustices that the community has suffered. Oxfam and the Australian public are still calling on ANZ to use its profits from its dealings with Phnom Penh Sugar to assist affected communities.

ANZ has links to other land grabs. ANZ has refuted its links to land grabs detailed in Banking on Shaky Ground – but not in any way that can be independently checked. For example, it says that it no longer has links to some companies, but does not say which ones. By contrast, other banks have disclosed information so we can research and verify, or refute, their claims.

ANZ’s ignoring land grabs is bad for business. In November Westpac and NAB joined companies like Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Nestlé and created new policies to manage the business risks of land grabs in the agriculture sector. Although more needs to be done, this showed that banks can act and should act. ANZ must now act to put in place policies and practices that show zero tolerance for land grabs and redress for affected communities.